Revealing the Absolute, Number One, Priority-A, Must-Have-or-YOU-LOSE Rule

Pete Jahn

I have been writing about, playing, judging and enjoying Magic, the Gathering for over a decade. I have played casual games around our kitchen table, and I have been to several Pro Tours and World Championships. I have played decks so broken they required banning, and fun decks so casual their only saving grace was a cute theme, or interesting artwork. I have played pretty much every constructed, limited and made up format I have ever heard of — and one rule is universal.

This is your opening hand. Is that great or what?

You would mulligan that? That’s $250 worth of cards right there! How can that not be good?

The reason is pretty obvious — it has no lands. You can’t play anything (that matters, of course.) And that’s the point.

Rule number one: get the mana right, or the deck sucks.

No matter how good the cards, the hand or the deck, if you cannot cast the cards and make it work, it is simply not good.

The most fundamental principle of Magic is that you use mana cast spells and creatures. Mana comes from lands (and mana artifacts, and creatures — but mainly from lands.) Until you draw and play lands, you are doing nothing. Well — generally doing nothing. If your opponent is playing lands and casting spells, you are doing something. You are losing.

Mana is a critical concern. All high level players and deck builders obsess about it. Here are just a couple examples pulled from premier articles on another website, all on the day I wrote this.

Pat Chapin, Innovations — Continuing to Examine Standard — “Bear in mind that this is just the list I am currently at, as of the day before the Grand Prix. It is very possible that I could change a couple of cards tomorrow morning, as I am not set on a build. The mana is the main thing up in the air.”

Adrian Sullivan, Amalgamated Swans for Standard — “So what makes up the breakdown of their mana? It almost sounds like an incredibly boring question, but when you consider that mana is two-third or more of the deck, this is actually a very critical question.”

Gerard Fabiano, Ten Tips for Drafting Alara Block — “3) There Is No “Correct” Amount Of Mana You Should Play – Decide When You’re Building Your Deck”

Kyle Sanchez, Down and Dirty — Cascading through PTQ Houston — “I have several changes in mind to plug up some holes in my overall strategy. I’m going to add more Vivid lands, as the mana is still on thin ice and I don’t like the Fire-Lit Thickets or Savage Lands. I might be going up to three Exotic Orchards, since having an extra painless City of Brass is an easy fix.”

You need to play enough lands, and the right lands. As a general rule of thumb you want your deck to be about 40% lands. This means about 24 lands in a 60 card deck. It means 17 lands in a 40 card deck. If your creatures cost a lot, you want more mana sources. In rare cases you want less — but only in very rare cases.

The 40% rule is by far the simplest. In some ways, it is simplistic. There are better ways of calculating mana. Let’s start by looking at how decks function, using two very simple decks:

One deck will have nothing but Forests and Grizzly Bears and one with nothing but Forests and Scaled Wurms. Pretend that they are not totally stupid — this is just an example. Let’s start with the 40% land rule. Both decks will have 36 copies of their creatures, and 24 lands, at least to start. Let’s look at what that means.

Grizzly Bears cost two mana to cast. If mana is 40% of the deck, that means that you should get two lands every five cards. By turn three, assuming the deck is on the draw, the Grizzly Bear deck will have four lands. That is enough to play two Bears a turn — but that is really more than the deck needs, since it will only be drawing one card a turn. By turn 12, assuming the game will go that long, the deck will probably have 8 lands in play — and one Bear to cast. That’s pretty useless.

The other deck is in worse shape. Scaled Wurm costs 8 mana. To get eight lands, with a 40% land ratio, the deck will have to draw, on average, 20 cards. Even on the draw and without a mulligan, the deck would be lucky to play a spell before turn 12. That is not a recommended strategy.

A better approach is to look at your deck’s critical plays — the cards that you need to play, and the turns when you need to play them. For example, years ago a deck called 9-Land Stompy had a lot of 1 or 0 casting cost creatures it needed to cast ASAP, and a Winter Orb (2 mana artifact) that it liked to cast around turn five. That Winter Orb was the critical play. That meant the deck needed one mana on turn one, and two on turn five. To do that, the deck needs to see 2 lands in 11 cards on the play, meaning it needs to run roughly 11 lands. Despite the name, the decks generally ran 10-12 lands, plus some free land fetchers (Land Grant — a card not yet available online.)

In short, the decks ran just enough lands to cast their critical spells, but not too many, to avoid mana flood.

On the other end of the spectrum, look at a deck like Pat Chapin’s Cruel Ultimatum-based 5CB. This deck not only runs 26 lands, it also runs 10 cards that draw more cards, so that Pat can reliably get the seven mana necessary to cast the Cruel Ultimatum around which his deck revolves.

Here’s some very basic math, based on a 60 card deck:

If you deck revolves around casting a

* two drop on turn two, play at least 15 lands.

* three drop on turn three, play at least 20 lands.

* four drop on turn four, play at least 22 lands.

* five drop on turn five, play at least 25 lands.

* six drop on turn six, play at least 28 lands.

And so on.

Lands are mana sources. So are creatures that generate mana, mana artifacts, land fetchers, etc. However, they are not always direct replacements. Take Gilded Lotus for example. It does produce mana, and it can accelerate mana production, but it also costs five mana to cast. If you plan on counting that as a land, you had better be running at least 25 lower costing mana sources, or you will see it stuck in hand too often. As a general rule, I count mana sources that cost two mana or less as half a land for the purposes of the above table.

The Mana Curve

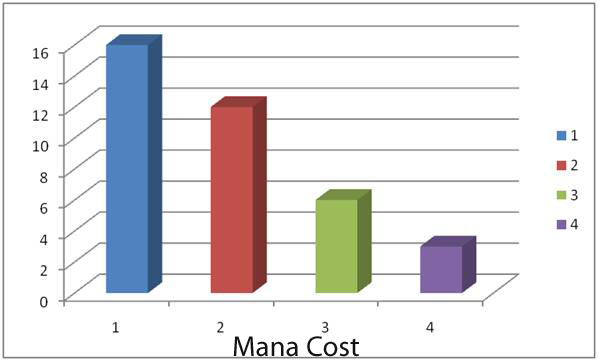

The mana curve was first heavily discussed following Paul Sligh’s PT win with a deck filled with bad, but cost effective, creatures. The Sligh deck’s plan was to use all of its mana every turn, and to use that mana very efficiently. The deck ensured that it would have a one drop on turn one, a two drop on turn two, and either a three drop or both a one and two drop on turn three. This means that the number of creatures needs to follow a curve — specifically, a declining curve. Here’s a graph of the original Sligh deck’s mana curve.

That’s a curve. The numbers actually combine spells and creatures, but it gets the point across. From a theoretical level, if the deck is going to be able to play, say, two-three 1 casting costs spells by turn three, it needs to have those three in hand by the time it hits turn three. That means it needs 2 1cc spells in the first 9-10 cards. To do that on average, it needs at least 12-13 of those cards in the deck. The deck also wants to cast 1-2 2cc cards on turns 2-3, and to do that it needs 7-12 copies.

On the other end of the spectrum, the deck does not want to waste draws getting cards it does not yet need. Therefore, the deck has very few cards that costs 4+ mana, because it can wait to cast them. These decks typically ran 20-22 lands, so they didn’t really expect to draw a fourth land until they had seen roughly one quarter of their deck. The low number of high casting cost cards meant that the Sligh decks tended not to draw those expensive cards early, or in numbers, so they avoided having thier hands clogged with uncastable cards.

Note that, in this deck, I am not considering Fireblast to actually cost six mana. In a Sligh deck, Fireblast cost just two expendable lands. Since the deck really only cared about playing one and two casting cost spells, only two lands were really necessary, so Fireblast was perfectly castable once the Sligh player hit four — two needed and two expendable — land.

Online, Fireblast is only playable in Classic and Pauper, but the concept of expendable lands is still relevant in all formats. In Alara block draft, and in Extended, we have lands that sacrifice themselves to fetch other lands (Panoramas and fetchlands, to be precise.) These lands fetch other lands — and this lets you both fix your mana and “thin your deck.” However, think about what thinning your deck means. It means increasing the “value” of your draws by increasing the ratio of spells to lands in your library — making it more likely that you will draw a spell, and less likely that you will draw a land.

Of course, if you want to draw land, this is not a good thing.

A while back, I drafted a Cruel Ultimatum and a Broodmate Dragon in an AAC draft. To support the stretched color requirement, I had some tri-lands and four Panoramas. However, I wanted to have 6 lands by turn six, to cast the dragon. Normally, to get that many lands, I would want to run around 18 lands, but because of the Panoramas, and a Frontline Sage to pitch spares too, I ran 20 land. I did not have problems with the dragon or Ultimatum stuck in hand, and I did well in the draft. Yes, that is a lot of land, and yes, it could result in being mana flooded, but that deck had to cast one of those two cards fairly early in order to win. The high land count made that possible.

COLORS

Getting enough lands is not enough — at least not if you are not playing a mono-colored deck. You need lands in both the right amounts and the right colors. Technically, losing because you are color screwed is different that losing because you are mana screwed, but neither are any fun. You need to avoid both.

One method of calculating the color split is to add all of the colored mana symbols in all of the spells in your deck, then calculate the ratio for each color to the total. For example, let’s assume that your deck looks like this:

3x Giant Growth (G for one, // 3 * G for all three)

4 Shock (R // 4 * R)

3 Fires of Yavimaya (1RG // 3 * R, 3 * G)

4 Kavu Climber (GG // 8 * G)

4 Wild Mongrel (1G // 4 * G)

4 Flametongue Kavu (3R // 4 * R)

4 Kird Ape (R // 4 * R)

24 Lands

Sure it’s a dumb deck. It’s just an example — and just 50 cards because it makes the math easier. I’m just lazy that way.

The deck has 15 Red mana symbols and 18 Green symbols for a total of 33 colored mana. That means that 15/33 or 45% of the lands should be Mountains, and 55 % should be Forests. With 24 lands, that means 11 Mountains and 13 Forests.

If you have some lands that tap for both colors, then subtract those out and ratio the rest. For the above deck, if you have 3 Shivan Oasis, 2 Karplusan Forests and 3 Savage Lands (all of which produce both R&G), then you can simply subtract the 8 non-basics from the 24 total lands needed, then just ratio the 16 basics. The would lead to the following mana base:

3 Shivan Oasis

2 Karplusan Forests

3 Savage Lands

9 Forest

7 Mountain

This simple method can be expanded to three or more colors, but use some judgment. The rule can break down at the extremes. For example, the other night I was in a Tempest / Tempest / Stronghold draft, and drafted a nearly black deck. I had lots of double and triple black cards — stuff like Dauthi Slayer, Evincar’s Justice and so forth. I was also splashing blue for two copies of Sift, to draw cards late game. I wanted to play 18 lands, and had something like 28 black mana symbols in the deck. The UU from the two Sifts meant that the ratio called for just 1.2 Islands. However, I wanted to be able to cast a Sift when I needed to, so I used a different calculation. I figured that I needed to be able to cast Sift by turn 6-8, at which point I would have seen about a third of my deck. That meant I wanted 3 Islands — way more than the ration, but the minimum for a serious splash.

The pure ratio effect can cause problems with splashes, and multiple colors. Once you have developed your mana base using a ratio, think about when you will be likely to draw that splash land, and whether the card will be useful at that time. That’s why I am generally willing to splash for removal, a bomb or card drawing in a draft, but rarely for minor creatures. If I have to wait to cast a card, it must be worth waiting for.

Here’s an example — in a recent Triple Reborn draft, I was Naya splashing three Swamps. I had a Putrid Leech, a Slave of Bolas and a Terminate to splash. Only the last two made the deck. The two removal spells are always good — they are only unwelcome if you have already lost, or have the game completely in hand. The Putrid Leech, OTOH, is best very early. I have no real interest in playing a Leech on turn 11 — I want it to hit turn two. However, if I am splashing the Swamps, the odds of having both a Swamp and the Leech in the first eight or nine cards is too small to consider, so the Leech did not make the deck.

The Suggest Lands Feature

MTGO has a new feature in the add lands pop-up in drafts and sealed events. It is the “suggest” button, that suggests a land mix for the deck. This is both really good, and really dangerous. I almost always click the button, but then I fix the result.

It appears that the suggest feature calculates the ratio for your deck, then applies it. So far, so good. However, it has two main drawbacks.

First, the feature does not calculate how many lands your deck should have. Instead, the deck simply looks at the number of cards you have already added to the build deck panel, subtracts that number from 40 and ratios the result. Thus, if you have 32 cards already in the deck and ask it to suggest lands, it will add 8 lands to the deck. Epic Fail that would be.

Second, the system does not understand split mana costs. It sees both halves, and uses them in the ratio. As a result, if your deck is straight RB, but has a few Sewn-Eye Drakes, the program will suggest some Islands. In triple Reborn, even when I was two colors, the program nearly always suggested a four or five different basic lands. I had to click the down arrow to remove them, then add a couple on color lands.

There might be a third problem — I don’t know for sure. I don’t know whether the suggest feature considers the lands and mana artifacts you already have in the deck. For example, if you have a couple tri-lands and a Panorama, I don’t know whether it sees these lands, and adjust the ration accordingly. It may — I keep forgetting to test this when I am in a draft. It would be easy enough — build a deck, add an on color Obelisk or land, hit suggest, then cancel that, change the obelisk or land and try suggest again. If the result is different, it calculates the colors the Obelisks can add.

Despite all that, I still use Suggest Lands. If I want a mana base that has 6 Forests, 4 Islands, 4 Plains and 3 Swamps, it is faster to click suggest once, then click a few up and down arrows than clicking to add all 17 lands individually. My view: use it, just don’t let it make your decisions for you. And check the results carefully.

So there you go — some basic rules to help you get the mana right. It would be nice to say that, once you get the mana right, winning is easy. Well, we all know that that is not true. The converse, however, is. Get the mana wrong, and winning is very, very hard.

So that’s it. Welcome to MTGOAcademy.

PRJ

“one million words” on MTGO